Daniel Griffith is a man with many titles: entrepreneur, farmer, husband, father, author, Accredited Professional, and Savory Hub Leader in Central Virginia (at the Robinia Institute).

It’s not unusual for Savory Hub leaders––given their entrepreneurial spirit––to bring more to the table than just a know-how of proper land management. Daniel, however, brings quite the unique and refreshing skillset to the Savory Global Network, putting words to paper that elicit the ethos of holism, regeneration, and connection to place.

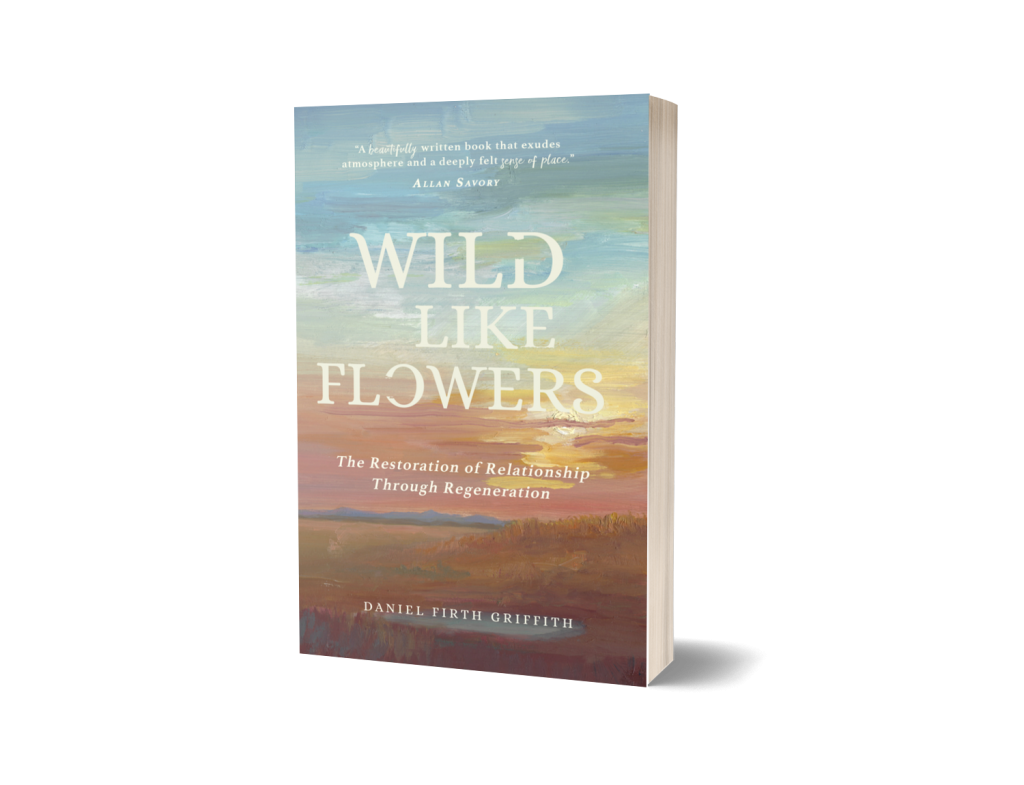

In his new book, Wild Like Flowers, Daniel has published a book on regenerative agriculture that doesn’t discuss how we farm, but rather why we farm.

Wild Like Flowers is a book of short stories and essay that utilize the magical gifts of being, of nurturing awareness and the community of all life, to prove the larger concerns of the modern agricultural and mainstream regenerative movement in lyrical and meditative prose that is a true celebration of life itself. It is a short book on a colossal subject; one that puts into words what so many in the Regenerative Movement are missing—the powerful and emergent force of Relationship.

Click here to purchase Wild Like Flowers direct from Daniel’s website, or you can find it anywhere books are sold.

Also, join us for a Q&A webinar with the author, March 10th at 1pm MT.

Below are a few select passages from the book:

“What is the Grass?” the child asks, handing the white-bearded poet a gathered handful. Whose? the bard postulates to himself, choking on the word as it comes out. He fumbles through the handful of blades and notices some fescue and orchard grass along with a hint of Indian grass. He smells it and is himself once more a child, laying underneath the meadow that herself rested between the harbor and brickyard of Huntington. Wild mint, yes, I know this spot. Lost in youth, he is trying to buy time, knowing all too well it is not for sale.

Why are they called blades? his mind rambles. Why is something so simple, so common and so daily, at the same time so entirely complex? Looking down into the eyes of curiosity itself, Walt Whitman replies, “I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic” that “sprouts alike… among black folks as among white.” Hieroglyphic sprouts, yes, something natural that symbolizes equality, good job Whit. But the child says nothing, can say nothing. The year is 1855 and the child does not understand why Kansas is bleeding or why John is upset. And Whitman’s internal ramblings linger in his throat, himself unsatisfied with his answer. He is still laying in the meadow smelling the wild mint.

Poetry may be the marvel masked in the dailiness of the mundane—novel phrases constructed out of ordinary words—but, in this moment, America’s bard struggles to find any words at all. And so he dives deeper. Stumbling through the depths of life itself, Whitman sees it and is awarded a new language altogether. Peering into the child’s eyes, he claims, “[Grass is] the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” Grass of Graves—simply magical.

The paradise that was invented and built by human industry eradicated the very utopia it sought to construct—and still seeks to construct. Learning to see is always much harder than creating what your eyes desire, and in time we shaped and bent and molded this earth to maximize industry and not to optimize function. The agent of escape from our place within Creation to our place outside of it was the machine, by design or metaphor—machine as desire, as the commanding force of application, or as the literal sword in the hand of the conqueror. Such mechanisms put distance between the user and the used, and Creation became material to be manufactured and molded according to human desires for leisure, singularity, and lawns. This Story of Separation, to borrow the phrase from Charles Eisenstein, put use above purpose, leaving the useless either sacrificed or neglected. The cult of progress has built a culture of separation that seeks monocultures as the epitome of human faculties and incult as the embodiment of corruption, all highlighted in the cultivation of the earth.

Using rewilded grazing and foraging animals within wild and seemingly chaotic management systems to drive ecosystem succession and habitat creation, our Wildland is attempting to restore the dynamics of wildlife and wild processes on our land. It is a vision that places human life a bit closer to being Native to this place. If only our guests could have been here for the sunrise. Up flung the light. I now know why.

Although we are building soil, sequestering carbon, restoring biodiversity, and regenerating our water-mineral cycles through the holistic and regenerative management of our place, we are also learning to stop and to listen and to see. We are learning to enter the Forest of Arden, to lose control of the court and submit ourselves to the counsel of the wild. Perhaps we are doing all of this because we first learned to stop—to stop moving and to start Being.

The Wildland is our canvas, but anywhere can be yours. That is up to you. We can learn to nurture awareness and thereby connection and community to achieve a truly holistic communion exactly where we are. That is another funny thing about life—it is often right where you are. Yes, life’s ordinariness is its most surprising characteristic. Daybreak’s preamble taught me that.

Daniel Griffith is a man with many titles: entrepreneur, farmer, husband, father, author, Accredited Professional, and Savory Hub Leader in Central Virginia (at the Robinia Institute).

It’s not unusual for Savory Hub leaders––given their entrepreneurial spirit––to bring more to the table than just a know-how of proper land management. Daniel, however, brings quite the unique and refreshing skillset to the Savory Global Network, putting words to paper that elicit the ethos of holism, regeneration, and connection to place.

In his new book, Wild Like Flowers, Daniel has published a book on regenerative agriculture that doesn’t discuss how we farm, but rather why we farm.

Wild Like Flowers is a book of short stories and essay that utilize the magical gifts of being, of nurturing awareness and the community of all life, to prove the larger concerns of the modern agricultural and mainstream regenerative movement in lyrical and meditative prose that is a true celebration of life itself. It is a short book on a colossal subject; one that puts into words what so many in the Regenerative Movement are missing—the powerful and emergent force of Relationship.

Click here to purchase Wild Like Flowers direct from Daniel’s website, or you can find it anywhere books are sold.

Also, join us for a Q&A webinar with the author, March 10th at 1pm MT.

Below are a few select passages from the book:

“What is the Grass?” the child asks, handing the white-bearded poet a gathered handful. Whose? the bard postulates to himself, choking on the word as it comes out. He fumbles through the handful of blades and notices some fescue and orchard grass along with a hint of Indian grass. He smells it and is himself once more a child, laying underneath the meadow that herself rested between the harbor and brickyard of Huntington. Wild mint, yes, I know this spot. Lost in youth, he is trying to buy time, knowing all too well it is not for sale.

Why are they called blades? his mind rambles. Why is something so simple, so common and so daily, at the same time so entirely complex? Looking down into the eyes of curiosity itself, Walt Whitman replies, “I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic” that “sprouts alike… among black folks as among white.” Hieroglyphic sprouts, yes, something natural that symbolizes equality, good job Whit. But the child says nothing, can say nothing. The year is 1855 and the child does not understand why Kansas is bleeding or why John is upset. And Whitman’s internal ramblings linger in his throat, himself unsatisfied with his answer. He is still laying in the meadow smelling the wild mint.

Poetry may be the marvel masked in the dailiness of the mundane—novel phrases constructed out of ordinary words—but, in this moment, America’s bard struggles to find any words at all. And so he dives deeper. Stumbling through the depths of life itself, Whitman sees it and is awarded a new language altogether. Peering into the child’s eyes, he claims, “[Grass is] the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” Grass of Graves—simply magical.

The paradise that was invented and built by human industry eradicated the very utopia it sought to construct—and still seeks to construct. Learning to see is always much harder than creating what your eyes desire, and in time we shaped and bent and molded this earth to maximize industry and not to optimize function. The agent of escape from our place within Creation to our place outside of it was the machine, by design or metaphor—machine as desire, as the commanding force of application, or as the literal sword in the hand of the conqueror. Such mechanisms put distance between the user and the used, and Creation became material to be manufactured and molded according to human desires for leisure, singularity, and lawns. This Story of Separation, to borrow the phrase from Charles Eisenstein, put use above purpose, leaving the useless either sacrificed or neglected. The cult of progress has built a culture of separation that seeks monocultures as the epitome of human faculties and incult as the embodiment of corruption, all highlighted in the cultivation of the earth.

Using rewilded grazing and foraging animals within wild and seemingly chaotic management systems to drive ecosystem succession and habitat creation, our Wildland is attempting to restore the dynamics of wildlife and wild processes on our land. It is a vision that places human life a bit closer to being Native to this place. If only our guests could have been here for the sunrise. Up flung the light. I now know why.

Although we are building soil, sequestering carbon, restoring biodiversity, and regenerating our water-mineral cycles through the holistic and regenerative management of our place, we are also learning to stop and to listen and to see. We are learning to enter the Forest of Arden, to lose control of the court and submit ourselves to the counsel of the wild. Perhaps we are doing all of this because we first learned to stop—to stop moving and to start Being.

The Wildland is our canvas, but anywhere can be yours. That is up to you. We can learn to nurture awareness and thereby connection and community to achieve a truly holistic communion exactly where we are. That is another funny thing about life—it is often right where you are. Yes, life’s ordinariness is its most surprising characteristic. Daybreak’s preamble taught me that.