“60 years. According to the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organization, that’s how many harvests we have left.”

According to Savory’s Director of Development & Communications, Bobby Gill, who spoke on the TEDx stage in Big Sky, Montana in January 2020, this is a wake-up call. And it’s not just for farmers, but environmentalists, vegans, soccer moms, conservationists, politicians… it’s for anyone who cares about life on this planet.

“Regardless of what you eat, if you care about our continued existence on this planet, then we must take care of the totality of this planet. That includes her oceans, her rivers, her forests, and yes… even her grasslands.”

Watch the video below.

A Correction from the TEDx Talk

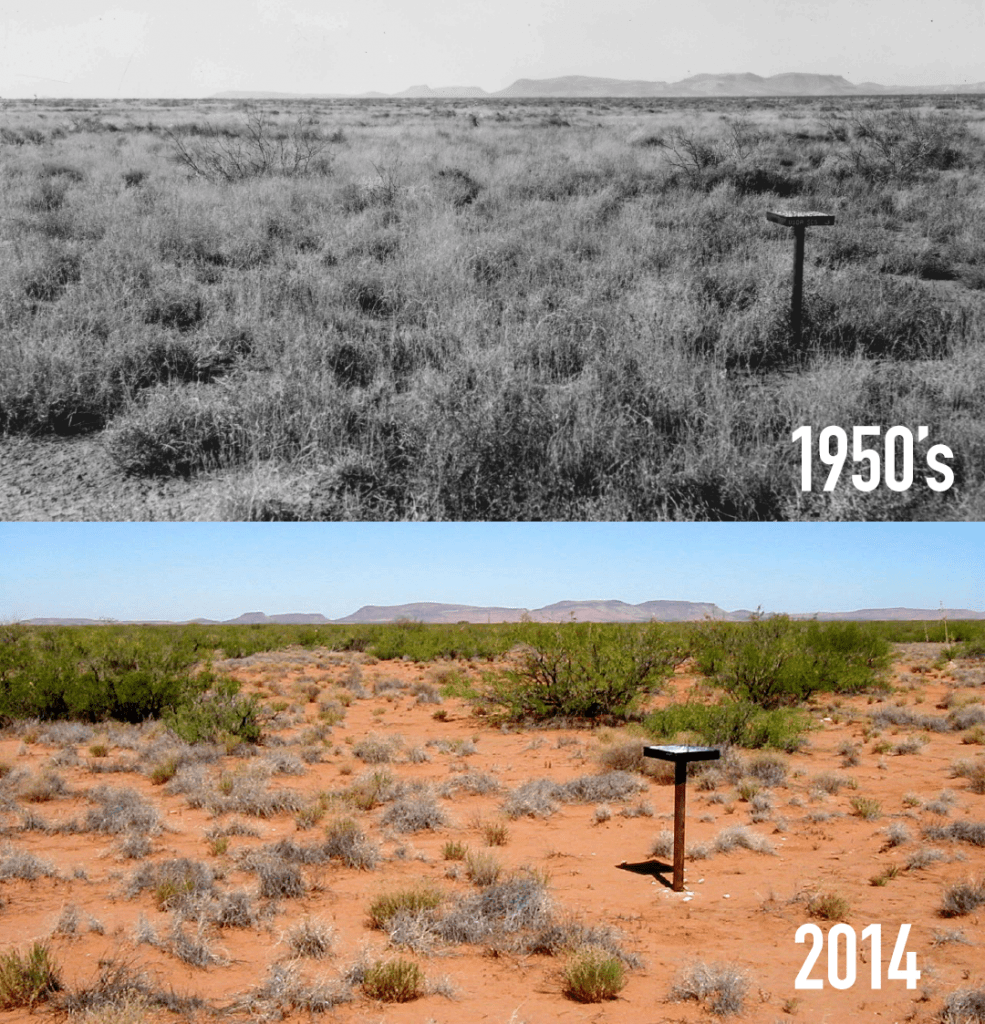

Hi everyone. Bobby here, writing to you post-TEDx and having realized an error I made on one slide. In talking to Allan Savory about the South Africa fenceline photo I presented (see below), he tells me I incorrectly identified the management type on the right side of the fenceline. Here is the photo:

In my talk, I discussed the right side of the fence as having no grazing whatsoever, an example of desertification that occurs in brittle climates when grazing animals are removed. As it turns out, the desertification on the right side of the fence is due to continuous grazing, not a lack of grazing. I was wrong, but here’s why both are a problem…

With continuous (or set-stock) grazing, multiple factors are at play that lead to land degradation. When spread out across a large and open pasture, animals tread lightly, their hooves no longer breaking up the hard and capped soils that would let water in. With continuous access and bite-after-bite of the same plants, grasses can’t fully recover and overgrazing occurs. For the remaining leaves and stems, they no longer get trampled to the ground, closer to the soil microbes that could break them down. Instead, they remain standing, dead, gray, and oxidized. Both the overgrazed and the oxidized plants die off, bare ground eventually taking over.

As mentioned in the talk, “when you divorce grassland from grazer, you have broken the natural cycle and the land begins to die off.” Here is an example of this desertification due to a lack of grazing:

References

Below are references to the scientific facts cited during the talk:

Quote:

“60 years. According to the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organization, that’s how many harvests we have left.”

Source:

“Generating three centimeters of top soil takes 1,000 years, and if current rates of degradation continue all of the world’s top soil could be gone within 60 years, a senior UN official said.”

Scientific American – Dec. 5, 2014 – reporting on World Soil Day

Quote:

“One-third of the Earth’s land mass is grasslands.”

Source:

“Grasslands are a major part of the global ecosystem, covering 37% of the earth’s terrestrial area.”

O’Mara 2012, “The role of grasslands in food security and climate change”

Quote:

“But our grasslands aren’t thriving – they’re turning to desert. In the literature, some say up to 70% of them.”

Source:

“Worldwide, some 70 percent of the 5.2 billion hectares drylands used for agriculture are already degraded and threatened by desertification.”

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

Quote:

“Researchers […] show that when you switch to Holistic Management, or Adaptive Multi-Paddock (AMP) Grazing as some call it in the literature, you can sequester 3 to 8 additional tons of carbon per hectare per year.”

Source:

“…we calculated an average of 3.0 t C/ha/yr additional soil organic carbon in the top 90 cm of soil over a decade in AMP grazing relative to commonly practiced heavy continuous grazing. […] With AMP grazing, relative to commonly practiced heavy continuous grazing, we measured higher C levels of 7.0 t C/ha/yr over 5 yr in Mississippi; 2.5 t C/ha/yr over 20 yr in North Dakota and Canada; and 0.5 t C/ha/yr in 20 yr in New Mexico, respectively.”

Teague 2018, “Managing grazing to restore soil health and farm livelihoods”

Quote:

“Experts generally agree that 350 (ppm atmospheric CO2) is roughly where we need to get back to if we want to stabilize this mess we’re in.”

Source:

“If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm, but likely less than that.”

Hansen 2008, “Target Atmospheric CO: Where Should Humanity Aim?”

Quote:

“Here’s a lifecycle analysis from White Oak Pastures, conducted by a third-party firm, showing all the greenhouse gasses going in and out of their farm. […] for every pound of beef that comes from their regenerating grassland, they’re removing 3.5 pounds of CO2.”

Source:

“The net result is that WOP beef has a carbon footprint 111% lower than a conventional US beef system.”

Quantis 2019, “Carbon Footprint Evaluation of Regenerative Grazing at White Oak Pastures”